JT and the Femme Queen Aesthetic

Or The Importance of Black Transgender and Cisgender Sisterhood

Feel like a fem queen

Feel like the cunty

Feel so pussy

Feel like a fem queen

You’ll never feel like me.

— “Feels Like a Fem Queen” by Kevin JZ Prodigy

Bitchеs on my dick, pretty like a transgendеr.

— “No Bars” by JT

I grew up on rap and hip-hop, I can’t remember a time when it didn’t run my life; Nicki Minaj was the first concert I went to at 14 years old, I researched and dug deep into the history of the OGs such as Lil Kim, Lauryn Hill, and my personal fave Foxy Brown, and as I’ve gotten older, rap has been my outlet for envisioning a life that is both powerful and extravagant. Feeling like a boss bitch was the goal and that still hasn’t wavered as I’ve gotten older. Even through my transition, it was rap and hip-hop that got me to celebrate and appreciate my transforming mind, body, and soul and I have the rap girls to thank for that.

The rap girls are in a league of their own. Women in hip-hop have been present since the genre’s inception, yet in the last five years, female rappers have been dominating the charts. Megan Thee Stallion, Flo Milli, and Doechii are some of the few femmecees (female MCs) who have been making a name for themselves in the industry with hits like “Savage,” “Never Lose Me,” and “What It Is” making waves across countless Black girls’ Spotify playlists. However, no one has made a bigger impact on the scene than JT of the City Girls.

Jatavia Shakara Johnson, known by her moniker JT, is a Miami-based rapper who’s been active in the industry since her debut with fellow rapper Yung Miami (Caresha) as part of their duo the City Girls. I first heard of the group in my junior year of high school when listening to their debut mixtape aptly titled Period where the line “I need a nigga who gon' swipe them Visas” became my go to anthem at 17 years old. What attracted me to the City Girls was their Dirty South, Miami bass sound, with outrageous and raunchy bars to match. From classics like the domineering “Where The Bag At” to the club hit “Act Up,” the City Girls brought a sense of bodacious fun and sexuality reminiscent of Diamond and Princess from Crime Mob and Salt-N-Pepa. Even with the violence of facing incarceration in 2018, JT has managed to carve a space for herself in the growing expanse of the music industry.

Teasing new sounds and creative lyricism, it’s on JT’s second solo single “No Bars” that contains one of the hardest lines I’ve heard from a rapper in a while, where JT raps confidently: “Bitchеs on my dick, pretty like a transgendеr.” In the months following “No Bars” release, JT has begun to publicly and verbally express her affinity and support for trans and queer individuals as well as sporting more campy looks, going to queer events, and simply “kiki’ing” with the dolls. Because of this, some folks are seeing JT’s growing support as a form of paying homage to the femme queens of past and present. But how exactly did we get here, what does this shift have to say about our wider culture as a whole, and how we as Black women can support and uplift one another?

Femme Queen Aesthetic

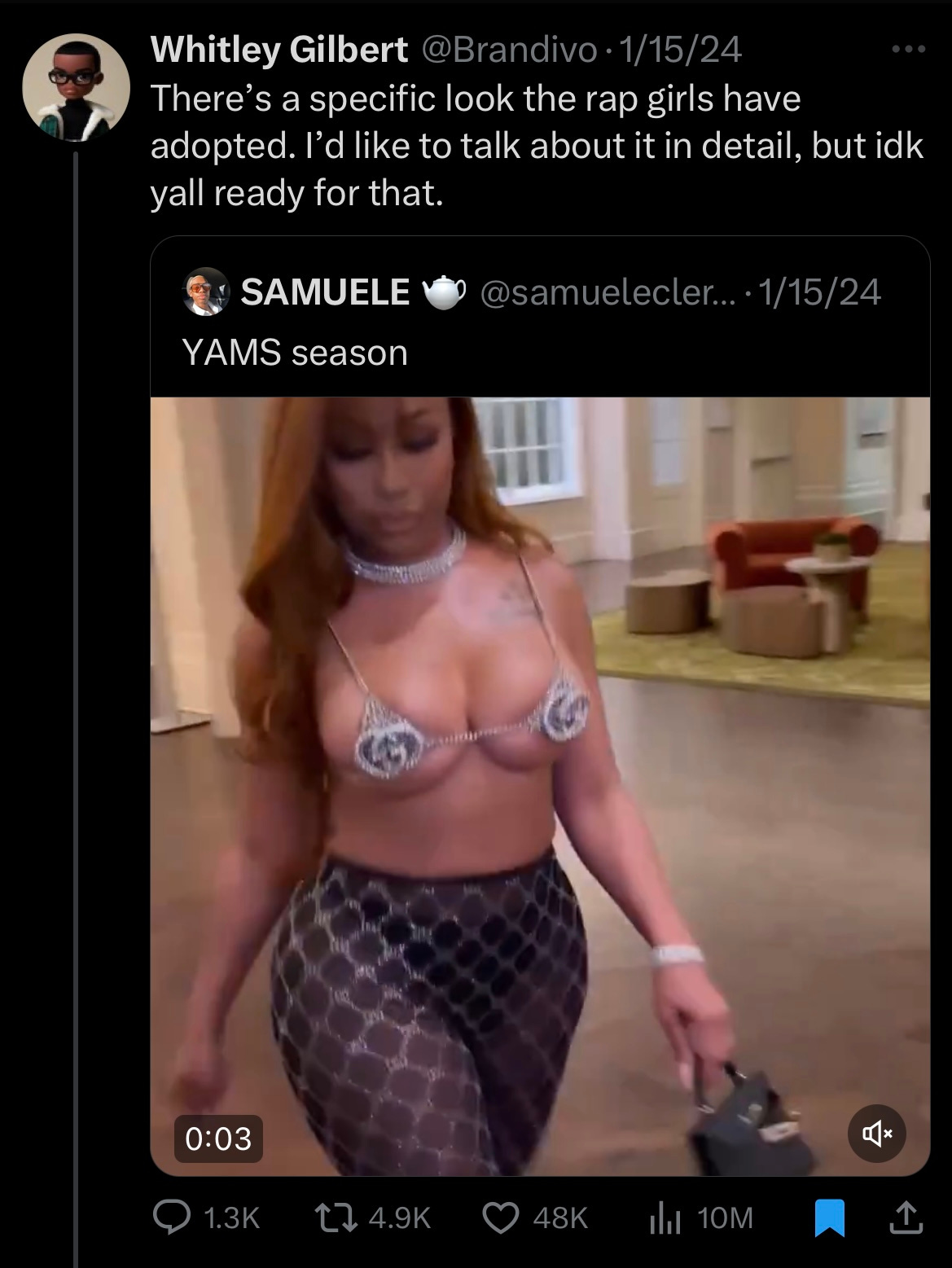

What prompted this specific blog post was the preceding tweet that signified a growing “aesthetic” that women in rap are currently partaking in. This was the first time I had ever seen or heard of the phrase “femme queen aesthetic” put together like that and with a basic understanding of what these two words meant I began to do some research into what this phenomena actually was. In an age of constant micro-trends and aesthetic movements, the “fem queen aesthetic,” based on its name, is derived from the Femme Queens (Trans women) of New York City Ballroom, specifically those who participated in the category of Femme Queen Realness where individuals are judged on their ability to pass as a woman (House of Luna). Now “passing” can mean many things, but as Ballroom Icon Stephaun Elite Wallace of The Legendary House of Blahnik explains, “Where a person is on the social transition or medical transition spectrum is not relevant.” Rather, “the degree of “realness” a person exhibits is a positive indicator of their appropriateness for this category.” Many prominent figures in the Ballroom scene have walked this category from Lola Ebony, Shanice Ebony, Kerri Mizrahi, and Amiyah Scott. Femme queens, and the category itself, have been a staple in Ballroom for decades and their legacy is unmatched both within and outside of the culture hence, the femme queen aesthetic—an aesthetic that seeks to achieve the look, style, body, and mannerisms of the Ballroom femme queens and dolls.

Traditionally, femme queens are Black women and per their name, hyper-feminine. Their expertise in the category involves them emphasizing their body as an asset for personal beauty. This can look like showing off the skin and bone structure of their face or flaunting their breasts towards the judges. Some may even go a step further, where in this clip, from Florida’s Renaissance People’s Choice Awards Ball, contestants wave their IDs and grab wipes to show how they are not wearing any makeup (note the use of “No Bars” in the background of the video). Essentially, to be a femme queen, one must be the pinnacle of glamor, extravagance, and a boss and none of this comes easy. It takes skill and work to be designated a femme queen in the Ballroom scene and a lot of what the girls do to look their best and snag a trophy is due to years of influence and innovation. Many of the makeup trends and practices we use today such as contouring were created and pioneered by Black trans women competing in this category. Writing for hypebae magazine, STIXX M describes the origins of contouring and its femme queen trailblazers' writing:

Interestingly, the art of contouring actually originated with femme queens who wanted to create a more feminine appearance by softening their facial features. By lifting the brow bones and flattening the Adam’s apple, these performers were able to create a more traditionally feminine look

In this same realm, gay makeup artists began styling the women they work for based on the women from the Ballroom and club scene such as makeup artist Kevyn Aucoin who then went on to write books on a variety of makeup techniques that were relatively unknown in popular culture at the time. All of these techniques were created to achieve a sense of “realness” to the performance of gender and femininity. By achieving “realness” femme queens were crafting unique visions and realities of what femininity meant for them, creating techniques and art that weren't being done by cis women in the culture until several years after the fact. Hence, à la Janet Mock, femme queens “redefining realness” is a testament to the creative iconography that Black women bring to cultural production.

In defining and redefining what it means to “be real” Black women across the gender spectrum continue to push the proverbial dial and transform the culture around them to bring something new, fresh, exciting, and innovative. Complicating the idea of what it means “to be real” acts as a rejection of the prevailing transphobic myth of the real, natural, or worse, biological woman. Thus, realness transforms from its meaning in relation to “passing” into something more far-reaching and expansive. Here, “to be real” is to be honest, raw, genuine, and authentic—your truest self. And what’s more real than the Black transgender woman who takes charge of her own destiny or the Black femmecee who engages in the pretty, pink, glamorous, and ultra-feminine, paying no mind to how people perceive her? At the end of the day, both of these women live for themselves and not society’s standards of what Black women should be.

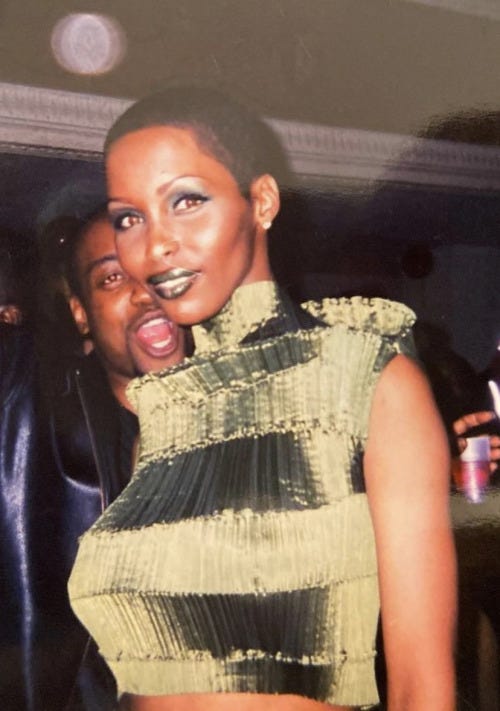

Hip Hop Feminism and Embracing Hyperfemininity

Hip-hop has often been associated with men and hyper-masculinity, however, that didn’t stop the women in the genre from being present and curating their own unique looks and style. Taking up both literal and figurative space, women wore what they liked and what they felt comfortable in, and by the mid to late 90s, women in hip-hop pushed the line even further. Compared to some of their predecessors, rappers like Lil Kim and Foxy Brown declined to adopt the baggy clothes of the previous decade; instead, they played up their femininity and sexuality in luxurious furs, colorful wigs, bikinis, high heels, pencil-thin brows, and dark lipstick (Angela Tate). These women brought a sense of style that was as defining and culture-shifting as their lyrics. These women showed how empowerment and femininity can coexist and the insistence of the femmecee to perform hyper-femininity as she chooses further challenges the stereotype of male domination in the hip-hop music industry. Moreover, by upping the camp factor when it came to their presentation, women in hip-hop were embracing their hyper-femininity in a glamorous and chic way akin to the femme queens who came before and during their time.

This crossing of cultural experiences and identities cultivates solidarity and joy in kinship as JT explains in an interview for Billboard, “I feel like transgenders are so pretty… They always fixed, they look good. I know a few personally. I call them all the time [and] ask them for, you know, little tricks and trades. They the girls.” JT’s insistence that the dolls are her “girls” and that she calls them to get advice and tips is a beautiful form of Black sisterhood. Now, I’m not the only one to see and make this connection between Black trans women and femmece’s both on- and offline. In her article “Seen In Legacy: How Femme Queens Inspired Modern-Day Female Rappers,” Kenyatta Victoria highlights the performance of hyper-femininity the rap girls do and how “The theatrics and charisma of Femme Queens connect with female rappers through their energy and aura, encouraging them to embrace their personas fully and deliver powerful, unforgettable performances.” This sisterhood pact is indicative of a relationship built on mutual respect between the women who are awarded as femme queens listening to women rap and empower them and the femmece’s themselves who then turn to the femme queens to learn tips and tricks of how to give a full performance of hyper-femininity and remain true to themselves.

Black Sisterhood as Solidarity and Kinship

In her Genius interview breaking down the lyrics for “No Bars” JT explains how she “just wanted to, out loud, give transgender women their flowers… They titties be sitting up. Their faces are beautiful. The makeup ideas and how hard they go for their beauty like, you know? I love it.” The dolls learn from their mothers and female icons to create a new hyperfeminine identity which is then replicated by the cis girls who also wish to perform hyperfemininity and embrace the camp, the glamorous, and drag art. This cycle represents the ways Black women contribute to each other’s identity-making.

However, there is no one way to be (much less look) trans nor is there one way to be or look like a woman. As Black women across the gender spectrum, we often do not get that luxury of defining our womanhood for ourselves. Writing in her dissertation Embodying Sisterhood: Community Politics of Black Cisgender and Transgender Womanhood Victoria E. Thomas explains how it is Black cis women’s duty to assert their privilege as cisgender and help in tearing down harmful institutions that subjugate Black trans women. Moreover, Black cis women must form coalitions with Black trans women in a world that is not kind to any of us:

Embodying Sisterhood contends with the ways race and gender organize our lives and posits that it is up to Black cis women to reorganize and resist dominant and binary understandings of Black womanhood. How can we value our Black womanhood, if we do not value Black trans women? (139).

Folks’ irrational fears that we’ve reached a point where we cannot tell the “biological” women from the rest is not only engaging in bioessentialism but frankly ridiculous. At the end of the day, who cares? There is not a single “look” or “aesthetic” that all women need or should embody. Yet, we can acknowledge when women, particularly cis women, take inspiration from trans women and ask that they continue supporting and uplifting us in solidarity. There is nothing wrong with seeing yourself in trans women and there is nothing wrong with being seen alongside us. So when JT raps proudly that she’s, “pretty like a transgender” she is declaring that these women are her sisters, they are a reflection of each other, and she has no shame in being seen as such.